Armin Theophil Wegner was born in Wuppertal (Westfalia) on 16 October 1886, and died in Rome on 17 May 1978. Doctor in Law, writer, poet, and deeply moved by the tragedy of the Armenian people to which he had been

eye-witness in Ottoman Turkey, Wegner dedicated a great part of his existence to the fight for human rights, and his literary and poetic output to the search for the truth about himself and his fellow men.

Armin T. Wegner, intellectual and refugee by Anna Maria SamuelliThe story of Armin T. Wegner is indeed a remarkable one: an intellectual brought up on his father's side deep in the authoritarian Prussian tradition, true patriot and soldier, but also writer and poet, enriched with that indestructible power that prevented him from falling in with the status quo, but instead exposed him to the fury of the ruling classes.

In Germany, the consolidation of National Socialism after the Thirties, was accompanied by the suppression of all avant-garde artistic expression and all that was out of step with the official line. This explains the emigration of over half a million German intellectuals after 1933.

Many were the places Wegner chose to live out his voluntary exile; many his attempts beyond the German border to carve out a space for himself in which he could write and express himself. As with other intellectuals, Italy was his final destination. This was not a safe choice as there the Fascist regime held sway. Neither could this choice bring serenity, given the inevitable nostalgia that accompanies the exiled. He could expect no more than a "precarious shelter" to which he added his own heavy load. His was a "journey of no return", caused by internal pressures. It was a restless journey of which he was more or less aware. It was to evolve into the testimony of and opposition to a regime insensitive to both human and cultural values.

It is not easy to speak of an intellectual whose song slowly died away in a foreign land, suffocated by memories of excruciating pain, of innocent and useless suffering. The experience of the genocide, as Varlam Salamov has written , no longer allowed literary production. But the real question was : what literature?

On 29 March 1916, as eye-witness to the genocide of the Armenian people, he wrote to his mother from Baghdad:

"Can I still live? Do I still have the right to breathe, to make plans for a future which seems so insubstantial, when all about me lies an abyss filled with the eyes of the dead?". Yet only the year before, on 2 November 1915 at his arrival in Constantinople, the tone had been that of a traveller impatient to set out and discover the world: "Now I hold the helm of my life in my own hands. I shall see Baghdad, the Tigris, Mossul, Babylon. I am fully aware of the choice I have made. ... I have become a soldier ... I have put my life at stake for my soul's sake." Not for fatherland, nor for mankind, but for himself alone did he set out to discover himself, to understand, to continue to nourish that vocation to art that from adolescence had driven him to observe the world with restless eyes, and to throw himself into ever new undertakings. The terrible experience on the Middle Eastern Front, followed by that of Nazi violence, forever marked the direction his life and work would take: "From time to time I fall back to sleep and sink into the depths of my dreams, and then, in a terrible and violent manner, in front of me looms up a work so dreadful that it must surely be the most pitiless ever written about human misery, and for all time."

Thus, Wegner, voluntary exile, intellectual betrayed by his discovery of the existence of Total Evil within the human heart, evil made more absurd and incomprehensible in its repetition, became a prisoner of a memory which did not fade with the years. The creative drive, the poetic vocation evolved into a need to bear witness. The survivors of the massacres and eye-witnesses hand on the memory of what really happened. They keep it alive in the hope of overcoming the ill of indifference, preventing the formation of new "grey zones", but at a very high price.

In 1916, back in Germany, Wegner "screamed" the Armenian tragedy to men unable to hear, marked as they were by the wounds of war. A drama had taken place and been consumed in silence. Each one was taken up by his own sorrow, unable to absorb the message of a common responsibility. Armin T. Wegner did not give in; he was sustained by lofty and noble sentiments; perhaps it was still possible to construct a world without evil from these wounds.

But these very wounds had put an end to any hope of change. The effects of the war swept away the fragile German democracy, and revolutions fuelled fear and advanced the unequivocal signs of the increasing barbarization of European civilization. The death wish which Wegner perceived as the end of any creative possibility, became widespread and penetrated deep into the secret corners of history. Where was man while these crimes were being committed? Even though historical memory is the duty of all and not the privilege of the few, it is not a safeguard; there is no guarantee for the future.

Wegner did not wish to witness another tragedy: if a genocide is liturgy, then there was nothing else to do but flee into exile and seek asylum elsewhere. Like many other intellectuals in exile, he had to face the consequences: not only, or, not so much because of the anxiety of nights fraught with horrors, but more for a soul irreparably divided between the banks of the Oder and the desert of the Middle East, between Armenia and Israel.

Only at the end of his life did he become aware of the value of this division, accepting it as his destiny.: " ... And even though I have lost much - and I am thinking of the many friends who disappeared during the course of my life and under dreadful circumstances - in recompense I gained something very precious, something which I had already perceived as an adolescent during my youthful wanderings. It is that in actual fact I no longer had a fatherland, but could feel at home anywhere. In Israel I lived in a wood in which a tree had been planted and given my name. In the Armenian capital, a street has been called after me, and at Stromboli on the ceiling of my study in the tower, there is a comforting phrase that goes: 'We have been assigned a task, but not allowed to complete it' ...".

Did the voice of the sea which Wegner heard from his tower at the foot of Stromboli free the voice of the poet, release the grip of memory, bestow calm to his spirit and have him feel, even a bit, at home?

Family and UpbringingArmin's father, Gustav Wegner, came from a family of rigid Prussian traditions. His mother, Marie Wegner, née Witt, became involved in the feminist and pacifist movements of the end of the century. In his autobiographical writings, Wegner recalled three episodes that left a mark on his life: his father's reading to him an account of the 1895 Armenian massacres in Turkey; his friendship with a Jewish school friend who, like him, felt different from the others; his throwing himself heroically into the Rhine to save a drowning girl. In his early years, the basic elements of his ethical code took form: the drive to independence in rebellion against paternal authoritarianism, social involvement as the discovery of others, and his civic courage.

His precocious work experience, (from 1903 to 1909 he temporarily abandoned his studies to live as a peasant), his wanderings around Europe (in 1913 he worked as docker in Marseilles), and his patronizing of literary cafés, liberal circles, and left-wing dissenters must be seen in this light. After his baccalaureate, he studied law and political science in Zurich, Paris, Berlin and Breslau where in 1914 he took his degree with the dissertation "The strike in criminal law".

The Experience of the War in the Middle EastThe Tragedy of the Armenian PeopleAt the outbreak of the First World War, Wegner enrolled as a voluntary nurse in Poland during the winter of 1914-1915, and was decorated with the Iron Cross. In April 1915, following the military alliance of Germany and Turkey, he was sent to the Middle East as member of the German Sanitary Corps. Between July and August, he used his leave to investigate the rumours about the Armenian massacres that had reached him from several sources. In the autumn of the same year, with the rank of second-lieutenant in the retinue of Field Marshal Von der Goltz, commander of the 6th Ottoman army in Turkey, he travelled through Asia Minor.

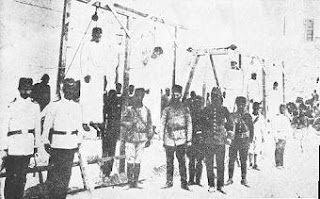

From the letters written between 1915 and 1916, a dramatic diary on the "way of no return" travelled by the Armenian people, the various stages of his movements in the Middle East can be traced: Constantinople, Ras el Ain, Mossul, Baghdad, Babylon, Rakim Pasha, Kalikie, Abu Herrera, Abu Kemal, Der es Zor, Rakka, Meskene, Aleppo, Konya, and back to Constantinople. Eluding the strict orders of the Turkish and German authorities (intended to prevent the spread of news, information, correspondence, visual evidence), the officer collected notes, annotations, documents, letters and took hundreds of photographs in the Armenian deportation camps. With the help of foreign consulates and embassies of other countries, he was able to send some of this material to Germany and the United States.

His clandestine mail routes were discovered, and Wegner was arrested by the Germans at the request of the Turkish Command. A letter to his mother of May 1916, describing the atrocities of the massacres, was intercepted, and he was put to serve in the cholera wards: "Armin T. Wegner must be utilized in such a way so as to do away with any desire of his to wander around Baghdad".

Having fallen seriously ill, he left Baghdad for Constantinople in November 1916. Hidden in his belt were his photographic plates and those of other German officers with images of the Armenian genocide to which he had been a powerless witness. In December of the same year he was recalled to Germany.

Civic and Literary CommitmentsDuring a leave of absence, but even more so after his final return home, Wegner met several times with the pastor Johannes Lepsius, founder of the "Deutsche Orient Mission", to whom he entrusted much of his photographic material. To spread knowledge of the Armenian tragedy, he made other contacts, such as Walter Rathenau, future Foreign Minister of the Weimar Republic, the publisher Helmut Gerlach, journalists and dissenters.

Between 1918 and 1921, he became an active member of pacifist and anti-military movements while continuing his literary and poetic activity. In January 1919, the first edition (numbered and signed) of his "Der Weg ohne Heimkehr: Ein Martyrium in Briefen" (The way of no return : a martyrdom in letters"), a collection of his letters from Turkey, was published in Berlin. It was a dramatic and firsthand account of the Armenian genocide and his tragic experiences in the Middle East.

On 23 February 1919, in the climate of hope generated by the political position of President Wilson, defender of minorities, Wegner's "Open letter to President Wilson" was published in "Berliner Tageblatt". This remains one of the most important documents of the sum total of publications dedicated to the Armenian Question. Wegner's appeal for the creation of an independent Armenian state came to nothing.

In 1920, Wegner married the Jewish writer Lola Landau, and in 1923 his daughter Sibylle was born.

In 1921 in Berlin, during the trial of Soghomon Tehlirian, (a young Armenian student who had lost all his family in the 1915 massacres, and wanted to avenge his relatives and his people by killing Tal'at Pasha, Minister of the Interior under the Young Turks and responsible for the genocide), Wegner testified without equivocating about the tragic events of which he had had direct experience. Thanks also to the evidence of other non-Armenians (Lepsius and Nansen) Tehlirian was acquitted. The documents of the trial have been collected in the book "Justicier du génocide armènien : le procès de Tehlirian". The preface is by Armin T. Wegner. Here he makes the distinction, as he does in the letter to Wilson, between the responsibility of the Turkish government and that of the Turkish people, who "would never have stained themselves with a similar crime". To prove this, Wegner cited cases of disobedience (today in the West called "civil") of Turkish officials who refused to carry out the orders of extermination.

In 1922 he published an important appeal for the rights of the Armenians entitled "Der Schrei vom Ararat" (The scream from Ararat), and in 1924 he began a novel based on the Armenian tragedy and on twentieth century Armenia which was to be entitled "The expulsion", but which was never completed. For this reason, he would claim the right to precedence in subject matter over Franz Werfel, author of "The forty days of Mussa Dagh". (cf.. Deutsches Literaturarchiv, Letter from Wegner to Werfel, 14.12.1932)

Imprisonment and EscapeWegner's activity as writer and civil rights militant became more intense with popular novels, stories, articles, lessons in European pacifist circles, travels. In 1927 he was invited to Moscow and, for the first time, visited Armenia which in 1922 had become one of the Soviet Socialist Republics.

In Germany, the rise of National Socialism revealed his human and intellectual isolation. He was classified as "Bolschevik intellectual", traitor to the ideals of German nationalism, and with other seventy-one writers was put on the black list under the category "Belle Lettres", compiled by the Ministry of Education and Propaganda of the Reich.

On 11 April 1933, immediately after the Nazi raid against the Jews, Wegner wrote an open letter to Adolf Hitler and had it delivered to the Braune Haus in Münich. It contained a clear protest against the inhuman and anti-Semitic behaviour of the Regime. For this courageous act, but especially because he had been labelled "fanatic pacifist" and German "left-wing sympathizer", he was arrested by the Gestapo, thrown into the basement at Columbia Haus, beaten and imprisoned. Transferred to three different concentration camps, Oranienburg, Börgermoor and Lichtenberg, he was finally released in the spring of 1934 after five months detention. He joined his first wife in London, and then in Palestine where she had emigrated with the daughter. They divorced in 1939 by common consent. Wegner was to write later about this period, "Germany took every thing from me, my home, success, freedom, work, friends, family, home and all that was dear to me. In the end, Germany took away even my wife. Yet this is the country I continue to love in spite of everything.!

Exile in ItalyBetween 1936 and 1937 he moved to Italy, first to Vietri where he met an artist of Jewish origin, Irene Kowaliska whom he had already known in Berlin. In 1945, she becomes his wife and they moved to Positano. With the racial laws of 1938, the climate of relative tolerance in Italy began to deteriorate. For security reasons on the occasion of Hitler's visit to Italy, Wegner was arrested with other refugee intellectuals, though for only a few weeks. A period of depression began at this time. The traumas from the period of his detention began to re-emerge, and the burden of isolation was experienced as the loss of his identity as a writer.

The day after Italy entered the war, Herbert Kappler ordered Wegner's arrest and he was confined in the camp in Potenza. He succeeded in reaching Rome, and because of his German citizenship went directly to the German Embassy. The order of arrest was withdrawn.

In 1941, a son Misha was born. From 1941 to 1943 Wegner taught German language and literature at the German Academy in Padua. He was listed as A. Theo Wegner in the faculty files and this prevented him, paradoxically, from being identified. With the liberation of 1943, Wegner returned to Positano where he remained until 1955 except for short periods in Stromboli and Rome. To make ends meet, he sold some of his possessions.

In spite of his cosmopolitan spirit, so deep were his German roots that he never fully succeeded in adapting to the life of exile, and for a long time he was unable to carry out his literary projects. He returned to Germany for the first time in 1952, but felt estranged in his native country which made a definite return impossible.

In 1956 on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, the press discovered his photographic documentation. The images that "unite dignity and suffering" caused a considerable stir for their intensity of expression and artistic quality. On this occasion Wegner published his essay "Parì luis : Das gute Licht" on the events of 1915.

RecognitionHis role as eye-witness to the Armenian Genocide and defender of the rights of the Armenians and Jews finally received international recognition. Besides the honours conferred on him by his native town in the German Federal Republic, in 1968 he was decorated with the title "Righteous Gentile" by the Yad Vashem in Israel and the Order of Saint Gregory in Yerevan, the capital of Armenia, where a street was named after him.

On 28 April 1968 Armin T. Wegner was invited to the Casa Armena in Milan where he shed new light on the first genocide of the twentieth century. Episodes hitherto unknown, and especially the images from his photographic archive left indelible memories.

The remainder of his life was divided between his literary activity and giving evidence at various international centres in Europe and the United States. In the poem "Der alte Mann" (The old man) he wrote: "My conscience calls me to bear witness. I am the voice of the exiled who scream in the desert". Before his death, he arranged the transfer of his entire literary production to the Archives of German Literature in Marbach in the German Federal Republic.

Armin Wegner died in Rome at the age of ninety-two on 17 May 1978. At Stromboli, on the ceiling of his study in the tower, the following words are carved: "We have been assigned a task, but not allowed to complete it".

Sources for the reconstruction of a biography of Armin T. Wegner• The Misha Wegner Archives. Deutsches Literaturarchiv, Marbach• Armin T. Wegner Gesellschaft, President: Dr. Martin Rooney, Berlin

• Gesellschaft für bedrohte Völker, co-ordinators: by Dr. Tessa Hofmann and Dr. Gerayer Koutcharian, Berlin

• S. Milton, "Armin T. Wegner, Polemicist for Armenian and Jewish Human Rights", in Genocide and Human Rights, NAASR, Vol. IV (1992)

• M. Rooney, Weg ohne Heimkehr: Armin T. Wegner zum 100. Geburtstag, Bremen, 1986

• K. Voigt, Il rifugio precario: Gli esuli in Italia dal 1933 al 1945, Firenze: La Nuova Italia, 1993

• W. Killy, Literatur Lexicon, München: Bertelsmann Lexicon Verlag, 1992

• M. Kindler, Kindlers Neues Literatur Lexicon, München: Kindler, 1992

• F.A. Brockhaus, Brockhaus Enzyklopädie, Mannheim 1994

[text from: Anna Maria Samuelli, Armin T. Wegner and the Armenians in Anatolia, 1915, Milano: Guerini & Associati, 1996]

http://gariwo.net/eng/armenia/wegner.htm#photowegner1